Over the last year or so, I’ve been trying to learn about various types and methodologies of testing. The Ruby community is pretty vocal about testing, so I felt out of place not knowing even the most basic of things. This post is intended to organize my current thoughts and hopefully provide some guidance for people on the same journey.

Who should read this?

I had to realize two things before I could start learning:

- I don’t know enough about testing.

- I need to know more about testing.

If you don’t fit into both of these categories, you probably aren’t reading this post.

If you know what “mockist” and “classicist” mean and you know which you are, you probably already know everything here. If you care, I generally take the “mockist” approach, and this post reflects that.

Otherwise, feel free to continue!

Why should I test?

The simplest answer is that testing allows you to have some degree of confidence that the code as written is right.

Less obvious is the fact that tests give you confidence to change code. Eventually, some part of the software will need to change while everything else should stay constant. For me, this point really hit home when I read Working Effectively with Legacy Code by Michael Feathers. I deal with lots of code that needs to be changed and I’m usually worried that my change might affect some conceptually remote piece of the software.

Maybe the hardest thing for people to believe is that tests can provide feedback on the design of the code. This is a core concept behind Test-Driven Design: if you listen to what your tests tell you about your code, you can make your code better.

Note that these three things cover the entire life cycle of code; correctness applies to the present of the feature, confidence comes into play when the feature is in the past, and design feedback sheds light into the future of your code.

What flavors of test exist?

Here is a list of the types of tests that I can think of purely off the top of my head, I’m sure there are lots more.

- Unit testing

- Integration testing

- Functional testing

- Acceptance testing

- Load testing

- Performance testing

- Fuzz testing

Those are all links to corresponding Wikipedia page; I don’t agree with every nuance listed on those pages, and some pages are unfortunately short, but the links provide the barest minimum of a start if you would like to learn more about each type of test.

I don’t tend to draw a hard line between integration, functional, and acceptance tests. If you need to know the difference, this Stack Overflow question has a pretty good breakdown. I think of acceptance tests as a superset of functional tests, which are themselves supersets of integration tests.

All I care to talk about in this post are unit and acceptance tests. I am not saying the other types of testing are not important. I am saying that I think that unit and acceptance tests are the most useful types of tests to start with.

I am nominally a programmer, and this post will exhibit that bias. I certainly hope that people approaching testing from a different angle can benefit from this post, but no guarantees are made.

How do acceptance and unit tests fit together?

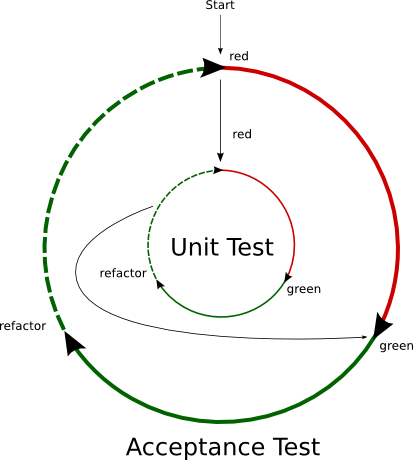

A great way to understand how acceptance and unit tests work in concert is to read The RSpec Book. If you are too lazy and/or cheap to read it, here’s one extremely salient picture:

The extremely abridged version is that you write an acceptance test for the feature you want. This test should be written from the point-of-view of the user and using terms that a user would use.

As you try to make the acceptance test pass, you will realize that you need to write smaller components to solve the larger problem. In an object-oriented language, these components will probably be objects. The test for each component is a unit test.

Acceptance tests

Acceptance tests tell you that the software as a whole does what it is supposed to do. It’s important to write acceptance tests as if you were the user. This makes it so that the test exposes the actual value of the code, explaining why the code even exists.

To write proper acceptance tests, you need to have complete control over the entire environment your software runs in. If you interact with a database, you must be able to change data in the database. If you need to be able to parse an empty RSS feed, then you must be able to create an empty RSS feed to test that functionality.

Because acceptance tests exercise the entire system, it’s very easy for them to be slow, but there are a few techniques that you can use to help keep your total time down.

Acceptance tests should cover the “happy path” of your software. If there are any extremely important failure cases, then cover those with acceptance tests as well. However, you don’t need to cover every possible case. For example, use unit tests to ensure that things that generate errors do so consistently, and then use one acceptance test to make sure errors are shown correctly.

Make sure that you minimize what data you need for an acceptance test. You probably don’t need to load 10,000 rows into your database just to make sure that a user can view their profile. Use the smallest amount of data you can get away with.

Don’t get lazy and reuse one giant piece of setup code for every test. This is an example of the tests telling you that your design is painful to use. In this case, a user would have to duplicate all of the steps in the setup in order to use the function you are testing. Maybe that’s the way it has to be, but try to make it easier on the user.

Unit tests

Unit tests have some exciting qualities for a developer. Generally, unit tests are fast and can isolate exactly the one thing that is broken. Achieving these goals takes hard work.

Limiting each unit test to one assertion enables isolation of faults. If a test fails, the name of the test by itself should serve to tell you exactly what went wrong. If you have multiple assertions, then you have to look at the failing line number to determine the real issue.

Mock objects

One way to achieve isolation and speed in your unit tests is to introduce mock objects. Mock objects are test doubles that surround the real code under test and assert on the messages sent between objects. Since they aren’t real objects, they can’t affect your test correctness, and they are extremely lightweight so they will be fast.

Seems easy to use mocks, right? Just create some dummy objects that responds to the necessary methods and returns values as needed. Then point the object under test at the mock objects, run the code, and assert that tested object has used any returned values correctly.

Here’s an example of doing that in Ruby. I’m eschewing using any libraries in an attempt to make the code as obvious as possible.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | |

Sorry, I lied to you; that last example was not a mock – although I thought it was for the longest time. The double shown is actually a stub. The key point is that a mock asserts messages are sent. The example above asserts a state.

Here is a test that correctly uses a mock:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 | |

This last example uses a mock to assert that the right messages were

sent. Note that we removed the foo accessor from the first class; we

don’t need it anymore! The state of the object is now kept where it

should be – inside the object.

The difference between stubs and mocks can seem subtle, but it is important. For a much richer discussion, read Mocks Aren’t Stubs by Martin Fowler.

I make no claim that this example is a good use of mocks, just that it is how mocks are to be used.

Object-oriented programming and mocks

This is all recent information that started to worm its way into my brain after watching Why You Don’t Get Mock Objects – you should watch it too.

The code example above may still have a problem. The Foo object asks

the Bar object for the value of quux and then manipulates the

result. This goes against the Tell, Don’t Ask principle, and

could be a warning sign of Feature Envy.

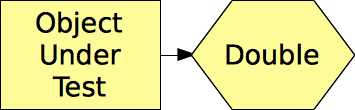

You should only mock collaborators. Collaborators are objects that are peers of the object under test. Collaborators should not be confused with objects that simply serve as implementation details. If you store a bit of state in a string or some integers, those are internal details and should not be mocked out.

Example of applying these ideas to real code

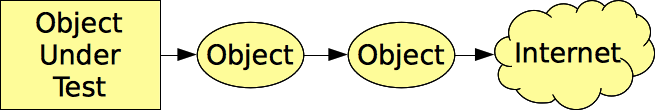

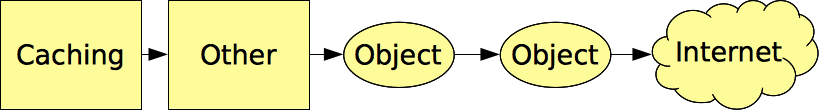

This is a real (but anonymized) feature and test example. We have a piece of code that manipulates data retrieved via HTTP. This retrieval can be fairly expensive, so we want to cache the final manipulated result. The code that does the manipulation and caching is separated from the HTTP call by a few intermediate objects.

Our current testing strategy is to provide fake data at the end of the chain, effectively short-circuiting the HTTP call. We also count the number of times that the HTTP call is made, and the test fails if the call is made more than once.

One obvious downside is that if any of the intermediate objects decide they need to make an HTTP call themselves, our test will fail. What’s worse is that the failure will seem to indicate that the caching is not working, so we will start debugging there. When we finally figure out that the test is “lying” to us, we will have wasted time and started to distrust our tests.

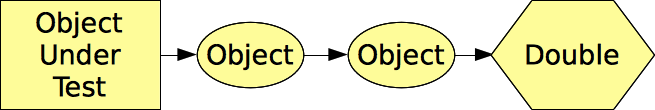

We can make the test better if we move the test double closer to the code under test. This lets us ignore all the other objects in the call chain – if one of these other objects does not behave properly, this test will not fail. This is no free lunch; there must be unit tests that focus on the other objects so you can tell when they break!

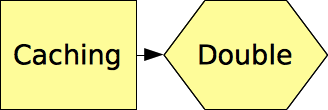

While writing the caching tests, we should notice that there are two sets of unrelated tests: one that checks that the core functionality works, and one that checks that the caching works. This should influence us to split the object apart (better known as the Single Responsibility Principle).

Splitting the caching into a separate object will allow us to test the caching behavior in isolation.

A handful of things to learn next

My learning isn’t over, and hopefully never will be. Here is a sample of some questions currently percolating in my brain.

Acceptance tests are often slow because they hit an external resource. Ruby has a gem called VCR (and Java has a clone called Betamax) that record HTTP requests and responses and then play them back during subsequent test runs. By definition, using one of these tools means you are no longer always doing true integration tests. However, the speedup is usually noticeable.

- When should you use this type of tool?

- What are the positives and negatives of this kind of tool?

- How frequently do you clear the cache of saved responses?

- Can the concept be easily extended to non-HTTP protocols?

Ideally, you should never add code simply to make something testable. At that point, you are adding complexity to a system that will not benefit from that complexity. My pragmatic side says that sometimes you have to add hooks only to be used for testing.

- Do you really need to add these hooks?

- Is there a general type of design that avoids the need for the hooks?

- Is adding this kind of hook worth it?

Things you should read or watch

The RSpec Book (book)

Although the book seems like it will only be about Ruby, it actually covers the concepts of testing thoroughly. Introduced me to the {acceptance,unit}-test cycle. Also contains practical information if you will be testing in Ruby.

Mocks Aren’t Stubs (article)

Provides an overview of terms used as well as examples to help separate the different concepts (in Java, but don’t be scared). Defines “classicist” and “mockist”; you don’t need to pick one or the other, but understanding them is vital.

Why You Don’t Get Mock Objects (video)

Session from RubyConf 2011 that started to clarify certain aspects of mocking and testing. Gregory Moeck also introduced me to the term “secondary teacher”.

Growing Object-Oriented Software (book)

On my list of books to order and read. I used to think that I understood Object-Oriented Programming, but recent developments have changed that belief. I hope that reading this can help guide me to a better understanding.

Working Effectively with Legacy Code (book)

Excellent information about how to take legacy code (defined as code without tests) and make it non-legacy. Clarified how tests let you be confident about changes. Provides heaps of practical advice.

Tell me what I’ve said wrong

I’m certain that I’ve said something that someone will disagree with. If you’d care to correct my false ideas, feel free to contact me via Twitter. If you think it will take longer than a tweet, create a blog post and let me know about it!

Edits

2011-10-11 9:27 EDT

Fixed bad link and cleaned up some poor wording.