At work, we are embarking on a grand new project, one that promises to involve quite a few engineers and take a good chunk of time. It is the quintessential Next Big Thing. So far, one or two prototypes of the new product have been developed (and demonstrated with positive feedback), but now it is time to really get our hands dirty.

Of course, by “hands dirty”, I mean that it is time to generate reams and reams of project plans and software designs, both of which will take an inordinate amount of time to create and then be underused and under-maintained. One old friend that popped up during project planning was the ever-popular Gantt chart.

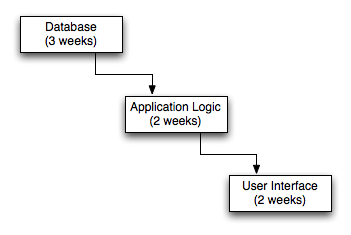

A simple Gantt chart

If you are unacquainted with Gantt charts, they are pretty straight-forward (as far as I have been able to determine). Gantt charts show how multiple components of a project can be scheduled together, accounting for dependencies between tasks as well as how long those tasks are expected to take.

A very simple Gantt chart

A very simple Gantt chart

As you see, each step requires completion of all previous steps before you can start on the next step. In this case, the project can be done in seven weeks (the critical path). Obviously, this is a highly simplified example, and bears no relation to reality, especially as I completely made it up. However, the astute reader can see how real-world projects might be coerced into Gantt chart form.

Mock objects to the rescue

Mock objects are simple pieces of code that stand in for other pieces of code. The most common times I have used a mock object has been when the real object is too complicated or slow to use in a test. However, there are other cases when they can be used, such as when the real object “does not yet exist or may change behavior”.

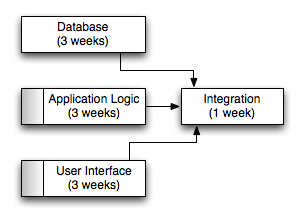

Previous Gantt chart modified to fully leverage mock objects

Previous Gantt chart modified to fully leverage mock objects

The heavy-handed dependencies of the first chart are gone, replaced by time to create suitable mock objects for the application logic and UI teams (represented by the gradients at left). For example purposes, I hand-wavingly say that creating these objects will take one week for each team. In addition, there is an extra week of “integration” after each team thinks they are done.

If this reorganization is to be believed, then we have reduced the time from start to finish for the project from seven weeks down to four. Obviously, this will save millions of dollars and allow the product to get to market that much faster.

Integration

Depending on how your teams work together, an after-the-fact integration step may or may not be needed. If each team works completely in isolation, then you will probably need a sizable chunk of time to make sure all the pieces fit together correctly. If your teams communicate and work together, then most thorny integration needs will have been hammered out along the way, and time spent purely on integration could be reduced.

In addition, if your teams have been working together, the interfaces between components are probably more ideal than if each group had developed sequentially. As the UI team realizes they need lower-level support to complete some feature, they can add that functionality to a mock object on-demand. In return, the application team can then look at the created mock objects to know exactly what interface and functionality is required, without worrying that they are writing code that won’t be used.

Not a panacea

Of course, mock objects are not a development silver bullet.

You need to be able to take advantage of the parallelization. If you only have one team or just one developer, it’s safe to say you wont see any time benefit from this process. For the moment, I am ignoring any additional benefits that mock objects might bring, such as reduction in testing or debugging time.

The total amount of development time is greater. The cumulative time for the sequential method is seven developer-weeks, but the parallel method takes ten developer-weeks. The counterargument here is that the start-to-finish time is less and your developer efficiency is much higher. If you have two teams sitting idle at any given time, you only have an efficiency of 33%. If everyone is working at the same time, the efficiency will be closer to 100%. This assumes that working 100% of the time is a good thing, which is debatable.

Teams in the middle of the dependency graph need to interact with other groups more. In the example above, the application logic team will need to communicate with both the database and UI teams, which can reduce the time available to work on the actual application logic. Even if you develop sequentially, this time still needs to be spent: when the application logic team is using the database, and then again when the UI team is using the application logic. The difference when working in parallel is that the time required is more obvious and the teams still view the code as mutable.

The programmers on each team need to be competent. This means they need to be able to think one abstraction level up and down, at a minimum. Your UI team has to be able to think similar to the application logic team sometimes, and the application logic team has to think like the UI team sometimes. Otherwise, the created mock objects could be completely fictional and impossible to create. If your developers do not meet this condition, you have bigger problems. Developers should always be aware of what goes on around them, and ideally everyone aims to be a full-stack developer.

Summary

Benefits

- Allows parallelization of “dependent” tasks

- Create more ideal interfaces

Potential problems

- Requires multiple teams that can work in parallel

- Total amount of work increases

- Teams in the middle must interact more

- Requires competent programmers

A note to the terminology-minded

I use the term “mock object” interchangeably with the more generic term “test double”. Martin Fowler has an excellent article that details some of the differences between different types of test doubles. Any type of test double should be able to help break the dependency chain; it is up to each team to decide which double is appropriate for a given situation.

Community feedback

EDIT 3:42 PM Groxx over at Hacker News points out that I am unfairly attacking the Gantt chart itself, and that realistically the problem is one of “organizational abuse”. In addition, the Gantt chart is quite capable of handling my second example. In my experience, most Gantt charts have looked more like my first example, so I tend to conflate the chart with the act of serialization of tasks.

My real point is that project planning often devolves into the concept of “we must code A before B before C”, but that by using techniques such as mock objects, we can break the (artificial) dependency graph.